This is a summary of a paper I presented at the International History of Public Relations Conference at Bournemouth on 8 July 2015.

Is the anti-smoking campaign the public relations campaign of the twentieth century?

It scores on awareness of the link between smoking and disease; it has achieved widespread attitude change around the issue of passive smoking; and it has reduced smoking from a majority to a minority habit.

Some might argue that the campaign has not succeeded because almost one in five of adults (19%) still smoke. But those behind the campaign had a different goal – to make smoking abnormal in society.

This was not initially a government campaign. It was initiated by a professional group of doctors – the Royal College of Physicians – whose only previous public campaign had been to lobby for an increase in the price of gin in 1725.

Nor was it obvious that doctors should take a stance on smoking. Some still smoked in the 1950s, and many felt that it was not their role to campaign against cigarettes as they were not a disease (though smoking could lead to disease).

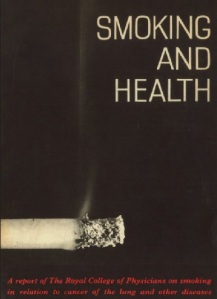

Change came with the election of Robert Platt to the presidency of the Royal College of Physicians in 1957. His greatest achievement as president was the report on Smoking and Health published in 1962. The catalyst for this report was a chest physician, Charles Fletcher, who had presented two BBC television programmes about health in the late 1950s and was a natural communicator.

Fletcher edited the report to make it comprehensible to the public and members of parliament (previous reports from the college had been written for medical practitioners only).

This report was launched on 7 March 1962 – Ash Wednesday – when the college held its first ever press conference.

This report was launched on 7 March 1962 – Ash Wednesday – when the college held its first ever press conference.

The morning press conference was well attended and the press release from this event provides an early and compelling example of risk communication. How to present the mortality risks from smoking to a roomful of journalists? Platt is reported as saying:

‘Those who smoke 25 or 30 cigarettes a day have about thirty times the chance of dying of [lung cancer] than a non-smoker does. Of course you might say it is still only the minority, about one in eight of heavy smokers, who died of the disease, and this is true. But supposing you were offered a flight on an airline and you were told that usually only about one in eight of their airlines crashed, you might think again.’

The report received extensive and largely positive press coverage – and interviews were given to the BBC and ITV (the only two television channels in the UK at that time).

Journalists accepted the evidence, though some questioned what action government should take.

The Daily Mail editorial from 8 March 1962 illustrates this ambivalence:

Risk in a cigarette

Men and women must decide for themselves whether to continue smoking or not. For the Government to try to do it for them would be an interference with individual liberty.

That is our first reaction the latest report on the relationship between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. It comes from the Royal College of Physicians, whose warnings should be taken to heart.

After years of argument there is no longer any doubt about the correlation between the smoke and the disease. The evidence is too overwhelming to be explained away.

We would strongly oppose the suggestion that the price of cigarettes should be made almost prohibitive. This is the wrong approach.

Smoking is a virtual necessity for millions of people and there would be widespread resentment (or pay demands) if a packet of 20 were put up to, say, 10s.’

To regulate smoking in public places is a better proposal. The foul atmosphere of cinemas and some theatres is a reproach.

But if restrictions are to be applied to tobacco, as they have to smoke from chimneys, why not also to car fumes? It is time some cleansing apparatus on exhaust pipes was made compulsory.

The tobacco manufacturers have spent a lot of money on research into lung cancer and have published the results without fear or favour. As they say themselves, still more is needed.

If they could find how to take the risk, but not the pleasure, out of cigarettes, they would do themselves and the public a great service.

The report presented seven recommendations for possible action by government:

- ‘more education of the public and especially schoolchildren concerning the hazards of smoking

- ‘more effective restrictions on the sale of tobacco to children

- ‘restriction of tobacco advertising

- ‘wider restriction of smoking in public places

- ‘an increase of tax on cigarettes

- ‘informing purchasers of the tar and nicotine content of the smoke of cigarettes

- ‘investigating the value of anti-smoking clinics to help those who find difficulty in giving up smoking.’

Looking back after more than 50 years, we can see that the aims of the report’s authors had been achieved. Indeed, in one case action has gone beyond what they had asked for (the health warning on cigarette packets has evolved into a blunt warning that ‘smoking kills’.)

The report sold well in the UK and the US and it received widespread and largely positive press coverage. But it did not initially lead to government action.

Some limited restrictions on TV advertising were introduced in 1965 and the Health Education Council (now Health Education Authority) was formed in 1968. It commissioned anti-smoking campaigns from Saatchi & Saatchi in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

So the initial response was disappointing, and after a brief decrease, numbers of those smoking (especially women) began to rise again.

The Royal College of Physicians decided to keep campaigning. A follow-up report ‘Smoking and Health Now’ was published in 1971 (this described the deaths from smoking-related diseases as a ‘holocaust’) and the College established the campaigning group ASH (Action on Smoking and Health).

Further reports followed in 1977 and 1983 – by which time attention had shifted to the issue of passive smoking.

Today, the UK has the strongest controls on tobacco of any country in the EU. Banning tobacco advertising, increasing taxes, banning smoking in public places have all helped to make smoking abnormal – but government was initially slow to act.

The campaign against smoking is now seen as a model for other public health campaigns (only this week doctors have called for an increase in the price of sweetened drinks). It marked a shift from doctors focusing on treating infectious diseases to campaigning on chronic (‘lifestyle’) disease, using the tools of public relations and public affairs.

Leave a comment